| |

They,

Including Minister Soga, Appeared Wearing Paekche Clothes the seminal

role of the Paekche people in the formation of the Late Tomb culture They,

Including Minister Soga, Appeared Wearing Paekche Clothes the seminal

role of the Paekche people in the formation of the Late Tomb culture

Wontack Hong

Professor, Seoul University

Kaya (Karak) vs. Paekche

According to Kim Ki-Woong (1986), the fact

that the early tombs were located on hilltops and had vertical-pit-style

chambers suggests that they correspond to the third or fourth century

Kaya (Karak) tombs, while the fact that the late tombs were located

on level plains and had horizontal stone chambers suggests that they

correspond to Paekche tombs. Furthermore, the ornaments found in the

early tombs are similar to those found in Kaya tombs, while the ornaments

found in the late tombs are similar to those found in Paekche tombs.

According to Kim, the oldest iron stirrups

excavated in Korea are mostly dated to the third and fourth centuries,

while the oldest stirrups discovered on the Japanese islands are mostly

dated to the fifth and sixth centuries.1>

According to Oka Masao, the Altaic kin term kara (having its cognates

in the Tungus dialect xala implying kin group) was introduced to the

Japanese islands at the beginning of the Yayoi period, and then another

term uji (implying “kin group” ul in Korean, and “descendants” uru in

Tungus) was introduced with the Altaic royal culture in the fourth century.

Oka apparently postulates two different waves of people from the Korean

peninsula.2>

According to the Dongyi-zhuan of Wei-shu

that was compiled in the late third century, since the men and women

of twelve Pyun-han states were very close to Wa (people), many of them

had tattoos.3> On the other hand, according

to the Liang-shu that was compiled in the early seventh century, since

the Paekche State was close to the Yamato (State), there were many Paekche

people who had tattoos.4> The fact that

it was the Pyun-han (Kaya) people who had commenced the 600-year Yayoi

era on the Japanese islands, and that it was the Paekche people who

had established the Yamato kingdom and commenced the 300-year (Late)

Tomb era, came to be recorded in the Chinese chronicles with such a

subtle differentiation of expression.Kitabatake Chikahusa (1293-1354)

was a political and ideological leader of the southern dynasty during

the period of the so-called South-North dynasty of the Yamato kingdom

(1331-92). He wrote a historical chronicle in 1343, and in the Oujin

(Homuda) section, he stated that those chronicles claiming that “the

people of old Japan were the same as the Three Han people” were all

burnt during the reign of Kanmu (781-806).5>

Modern historians may well pay attention

to the fact that Kitabatake made such a statement specifically in the

Oujin section, and then might well ask themselves why. Drastic Changes

in CostumesThere occurred drastic changes in costumes by the Late Tomb

Period. A large proportion of the haniwa male figures are dressed in

jackets and trousers, as depicted in Nihongi for Amatersu and in Samguk-sagi

for King Koi.6> Kojiki and Nihongi record

the arrival of tailors from Paekche during the reign of Oujin.7>

Lee (1991: 741) observes that the Chinese chronicles record differences

between the clothing of the Korean peninsula and that of the Japanese

islands for the early [Yayoi] period, but record similarity between

them for the later [Kofun] period.

The Bei-shi records that men and women

in the [Late Tomb Period] Japanese islands wore shirts and skirts; the

sleeves of men’s shirts were short; and women’s skirts were pleated.

At this point, the Bei-shi specifically mentions that “in older days”

men wore a wide seamless cloth on the body.8>

Indeed, the Dongyi-zhuan has recorded that the clothing of [Yayoi] Wa

people is like an unlined coverlet and is worn by slipping the head

through an opening in the center, and that their clothing is fastened

around the body with very little sewing.9>

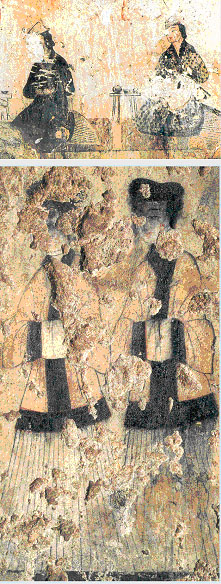

The paintings in the Takamatsuzuka tomb show the women wearing long,

lined jackets and pleated skirts. Kidder (1972) states that: “The costumes

of the women make it abundantly clear that Korean women are shown here.”

According to the Bei-shi, Zhou-shu, and Sui-shu, the attire of Paekche

men was very similar to that of Koguryeo men, both wearing caps with

feathers on both sides. The Paekche ladies wore jackets with ample sleeves

over the skirts.

Zhou-shu records that unmarried Paekche

women wore their hair in plaits gathered at the back but left a tress

of hair hanging as a decoration, while the married women formed two

plaited tresses of hair which were turned up. Bei-shi echoes that unmarried

Paekche women twisted their hair into a chignon and let it hang at the

back but the married ones twisted their hair upward in two parts. Sui-shu

similarly records that unmarried Paekche women twisted their hair into

a chignon and let it hang at the back while the married ones separated

their hair into two parts and placed them on head. Neither Bei-shi nor

Sui-shu mentions a chignon for Koguryeo women. The description of “hanging

at the back” in Bei-shi is specifically used for Paekche women.

If we examine the hair-styles of the ladies

in the Takamatsuzuka paintings, it is clear that they are the hair-styles

of Paekche ladies described in Sui-shu and Zhou-shu. Their hair-styles

are very different from those of the ladies-in-waiting appearing in

the fifth-century Koguryeo Tombs.10>

Nihongi records that on January 15, 593, relics of Buddha were deposited

in the foundation stone of the pillar of a pagoda at H?k?ji; and the

Suiko section of Fus?-ryakuki (compiled by the monk K?en during the

early thirteenth century) records that, on that occasion, some one hundred

people, including the Great Minister Soga Umako, had appeared wearing

Paekche clothes, and the spectators were very much delighted.11>

The chief of the Research Division of Sh?s?-in,

Sekine Sinryu, examined 60 pieces of ancient clothing and concluded

that the ancient clothing of Korea and that of Japan were exactly identical.12>

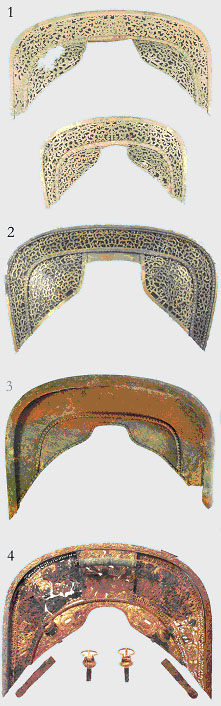

The Fujinoki SarcophagusThe stone chamber of the Fujinoki Tomb was excavated

in late 1985 and early 1986, and the sarcophagus itself was opened in

late 1988. The human remains were identified as a male adult between

20 and 30 years of age (of his secondary burial) and a woman. About

10,000 items (counting the beads in lumps) including a gilt-bronze crown,

two pairs of gilt-bronze shoes with dangling fish ornaments, two pair

of heavily gold-plated bronze earrings, a bronze belt with two silver

daggers stuck inside, 416 gold pendants, a pair of gilt-bronze half-cylindrical

leg guard pieces, 4 bronze mirrors, 5 swords, and 47 pieces of the brownish-grey

ceremonial Sue ware, were recovered.

A large quantity of horse-trappings was

piled on the chamber floor behind the sarcophagus. The tomb has also

yielded about one thousand slats of iron armor, iron arrows, and arrowheads

(see Kidder, 1989). One mirror has inscriptions of three characters

(yi zi sun) implying “May the owner have an abundance of descendants”

exactly like the mirror from the Paekche tomb of King Mu-nyung (d.523).

According to Kidder, “most gilt-bronze crowns found in Japan were made

in Korea.” Kidder believes that the

Fujinoki

objects are very similar to Paekche material, specifically the grave-goods

from the tomb of King Mu-nyung, and perhaps most of them actually came

from Paekche.Kidder (1989) contends that Fujinoki is the tomb of Sushun

(r.587-92), Sh?toku’s uncle assassinated by Soga Umako (d.626), inadvertently

exposed to public view through misidentification dating from Tokugawa

or Meiji periods. A document dated Emp? 7 (1679) that was found in an

old chest in S?genji, a sub-temple of H?ry?ji, refers to the mound specifically

as the Misasagi-yama of Emperor Sushun. According to Kidder, Sushun’s

name still appeared in this connection in documents until 1872, and

the term Misasagi itself continued to be used into the early 1940s.

Items originated in the Korean peninsulaFarris (1998: 68-70) summarizes

the materials, technologies, and religious and political systems that

flowed from the Korean peninsula to the Japanese islands during the

entire Tomb Period. Fujinoki

objects are very similar to Paekche material, specifically the grave-goods

from the tomb of King Mu-nyung, and perhaps most of them actually came

from Paekche.Kidder (1989) contends that Fujinoki is the tomb of Sushun

(r.587-92), Sh?toku’s uncle assassinated by Soga Umako (d.626), inadvertently

exposed to public view through misidentification dating from Tokugawa

or Meiji periods. A document dated Emp? 7 (1679) that was found in an

old chest in S?genji, a sub-temple of H?ry?ji, refers to the mound specifically

as the Misasagi-yama of Emperor Sushun. According to Kidder, Sushun’s

name still appeared in this connection in documents until 1872, and

the term Misasagi itself continued to be used into the early 1940s.

Items originated in the Korean peninsulaFarris (1998: 68-70) summarizes

the materials, technologies, and religious and political systems that

flowed from the Korean peninsula to the Japanese islands during the

entire Tomb Period.

First, items essentially originated in the peninsula

such as iron ore and iron-working techniques, the cuirass, the iron

oven, bronze bells, court titles and surnames, the district, measurements

for the field pattern system, and mountain fortifications.

Second, items from China that were transmitted with

some alteration or refinement, such as the ring-pommeled sword, (U-shaped)

iron attachments for farming tools, pond- and canal-digging technology,

stoneware, silk weaving, the idea for service and producer units (be),

law codes, and writing.13>

Third, items that were transferred with slight changes,

such as lamellar armor, horse trappings, stone-fitting methods and tombs,

gold and silver jewelry, Buddhism, and the crossbow. Farris

(1998-70) states that: “Taken together these three modes of transmission

reflect the seminal role played by peninsular peoples in the formation

of Japan’s Tomb culture.”

APPENDIX: THE UJI-KABANE (SHI-SEI)

AND BE SYSTEM

According to the Zhou-shu, Paekche maintained a system

of twelve Be (Bu) which served the court as palace functionaries and

ten Be which filled government officies (as divisions of the government

at large). The former included the Be of grain, Be of meat and butchers,

Be of inner repository and storekeeping, Be of outer repository, Be

of horses, Be of swordsmiths, Be of medicine, Be of carpenters, and

Be of law. The latter included Be of military service, Be of education,

Be of civil engineering, Be of judicature, Be of registry, Be of diplomacy,

and Be of finance and taxation.14>

The Yamato kingdom was established on the foundation

of a politico-social system called Uji-Kababe. The Yamato ruling clans

were grouped into a large number of extended pseudo-kinship units, called

Uji, which acquired clan names denoting the place of their domicile

or their occupation. Be groupings represented the hereditary occupational

groups serving the Yamato court, under the command of Uji chieftains

with Kabane titles. Kabane were titles (prestige order) conferred on

Uji chieftains to show their status in the Yamato court. Neither Uji

nor Be was a kinship group based purely on blood ties. Both were functional

groups including persons without blood relation that were established

in the form of extended family units for practical purposes.

The aristocratic Uji chiefs were entrusted with the

control of Be groups that furnished goods and services to the court,

undertaking farming, land reclamation, fishing, weaving, pottery making,

divining, and production of craft goods and iron weapons. Each Uji was

assigned a different role and task.15>

According to Inoue (1977), the term Uji derives from the Korean Ul and

the Mongolian Uru-q, denoting a patrilineal group, and the use of the

Chinese character Be “was presumably influenced by the twelve court

offices (Bu) of Paekche.”16> Kiley (1983)

is more specific: “The use of Kabane titles, like the division of political

jurisdictions into Be, was adopted from Paekche. It is quite likely

that the institution of Be was the beginning of the Uji.

The primary means of controlling the people in the pre-Taika

period was Be system. The development of Be was stimulated by that of

Paekche. It embodied a distinction between the inner court, i.e., the

King’s domestic household, and the outer court or government at large,

and each court had its own treasury. This distinction, another adaptation

of Paekche institutions, made room for the development of more purely

political offices in the national administration.”17>

Be was the service group organized first by the people who came from

Paekche, fashioned after the Bu (Be) function in Paekche.

There were some Be groups that belonged to the royal

family, but most of them belonged to the Uji. The Uji chiefs who were

in control of the Be groups occupied the core positions in the Yamato

court. Uji was the means of effectively maintaining and utilizing the

Be groups. The Be system that constituted the foundation of the Uji

was indispensable for the Yamato kings to act as the supreme rulers.

According to Nihongi (N1: 365), Y?riaku assembled all

the Hata people and gave them to Lord Sake of Hata (Hada no Miyakko)

who, attended by excellent Be workmen of 180 kinds, could soon pile

up fine silks to fill the Court. Y?riaku then dispersed (ca. 472 AD)

the Hata clan throughout the country and made them pay tribute in industrial

taxes.18> The Hata and Aya clans, the

two largest clans that came over to the Japanese islands from Paekche

en masse during the reign of Oujin, were entrusted not only with sericulture,

weaving, metallurgy, and land development but also all kinds of administrative

duties including diplomatic services, supervision of government storehouses,

record-keeping, collection of taxes and disbursements of government

resources.

These two clans, in particular, enabled the Yamato court

to function as a respectable nation-state. According to Nihongi, when

Y?riaku went on a hunting expedition, he wished to cut up the fresh

meat and have a banquet on the hunting-field. The Queen was obliged

to establish the Fleshers’ Be on the spot for Y?iaku with three stewards

of her own. Following the Queen’s initiative, the Ministers, one after

another, were obliged to contribute some of their stewards to the Fleshers’

Be.19>

What this story tells us is that a Be can be established

with as little as three persons as the occasion demands. This also implies

that the Yamato people were much more flexible and informal than the

Paekche court in establishing a Be as the occasion requires. The Yamato

court had maintained Yama-Be (gathering such mountain products as chestnuts,

bamboo and vines), Im-Be (performing religious services), Haji-Be (making

haji and haniwa), Kanuchi-Be (producing iron weapons), Nishigori-Be

(weaving silk fabrics), Kinunui-Be (sewing clothes), Umakai-Be (raising

horse or producing cattle feed), Kuratsukuri-Be (making saddles), Toneri-Be

(performing miscellaneous tasks and policing duties), Kashiwade-Be (working

in the imperial kitchens), Saeki-Be (performing military services),

and so on. 20>

?bayashi (1985) states that the “important factor for

the maturation of Uji is the influx of influence from Altaic pastoral

cultures into the Japanese archipelago, thus introducing some new kin

terms of Altaic provenance… This process went hand in hand with the

penetration of Puyeo and Koguryeo culture into southern Korea. … personal

ornaments of glittering gold from some fifth-century kofun indicate

the arrival of the royal culture of Altaic pastoral people via the Korean

Peninsula. Some myths and rituals centering on the kingship in ancient

Japan with Koguryeo and Paekche parallels surely make up another link

in the same chain.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

http://www.EastAsianHistory.pe.kr http://www.WontackHong.pe.kr.?2005

by Wontack HongAll rights reserved

[footnote] [footnote]

1> See Kim Ki-Woong (1986: 76, 88-9, 96-97, 99-101,

105-106, 112 120-1, 129).

2> See ?bayashi (1985: 13-14).

3> ??? ?? ??????? ??? . . . ???? ???

4> ?? ?? ?? ?? . . . ???? ?????

5> ?? . . .?????????????????????????????????????

????? ???? ????? (Tokyo: Kyuko, p. 28)

6> ????. . .???? (NI: 105) ???. . .?????? ??? ??????

(S2: 29-30)

7> ?? ??? ????????. . .?????????? (NI: 371) ??????????

???? (F: 290) ?? ???????? ?????(K: 248)

8> ?? ???? ?? ??????. . .???...??? ????? ???? ????

??? ???. . .?? ???? ???? ????… ?? ??? ???????

9> ??? ?? ??? ?. . .???? ????? ??? ?????? ????? ????

???? Ishiyama Akira (KEJ: 1.329) notes that: “Engravings of human figures

appearing [to be of the] Yayoi period [on] D?taku (bronze bell-shaped

ritual objects), excavated in what is now Kagawa Prefecture, depict

men wearing a sort of poncho.”

10> ?? ???? ?? ??? ? ??? ?? …??? ?? ?????…??????…?

???? ???? ??? ? ???? ?????? ??? ?????? ?? ???? ?? ???? ??. . .?????

?????.. ????? ??? ????? ???? ?? ???? ?? ???? ?? ??. . .????????…?????

??????? ? ????

11> ?? ????? ???? ? ???????? . . . ??? (NII: 173

) ???? ???? ???? ??????? ???? ???????? ???? ?? ???? ????? ????

12> See Lee (1991: 742-5).

13> According to Farris (1998: 82), the “reservoirs

for watering rice had been less important in China, where rivers kept

millet fields and rice paddies moist the year round.”

14> ?? ???? ?? ???? ??? ?? ???? ???? ???? ??????

?? ?? ??? ??? ?? ?? ??? ?? ?? ?? ??? ?????? ??? ??? ??? ??? ?? ??? ??

??? ??? ????? ???? ??? ?? ?? ?? ?? ????? ???????? ????? According to

Hsiao (1978, 38), many high-ranking court offices of the centralized

and bureaucratic Qin and Han dynasties originated in the needs of the

palace: “The position of prime minister (zai-xiang) originated from

the chamberlain of the royal family, and the so-called nine ministers

likewise evolved from the domestic staff of the royal family.”

15> Hirano (1977) contends that “a unified state

in Japan first came into being in the late fifth century on the basis

of the Be community system … Be system can be considered as representing

the basic socio-political structure of the primitive Japanese state;

at the apex was the Yamato sovereign, who had secured the allegiance

of powerful Uji chieftains. Below them were the numerous Be service

groups, who provided labor and goods.” By the sixth century, the imperial

clan created directly subordinate agricultural Be in the countryside

at the expense of local Be.

16> Farris (1998, 101) notes the fact that Tsuda

S?kichi had already contended that the word “Be” was derived from the

Paekche language.

17> Kabane usually constituted the final element

present in clan surnames. (There were clan names lacking kabane element.)

Barnes (1988: 29) states that: “The names of several of the standard

[Kabane] ranks have Korean origins and were probably introduced in the

mid-fifth century along with the Kabane idea of systematic ranking and

many other innovations. Moreover, many of the Uji holding Kabane ranks

were themselves of Korean descent.” According to Aoki (1974, 41), “Homuda

(Oujin) recruited his lieutenants from the village chieftains in the

growing delta. He called them Muraji, a term of distinctly Korean origin,

meaning village chief.” Muraji rank was for the important non-royal

Uji and generally derived their names from occupations. Omi rank was

for the lesser off-shoots of the royal family and usually employed local

place names. A Great Omi and a Great Muraji were the chief ministers.

18> ?? ??? ????? ???? ????? ????????? ?????? ????

?? ??? ? ?????? ????? ???? ?495

19> ?? ?? ...????? …???? ???? ???? ??????...????

???? ????? ???? ?????? ?? ???? ????????? ?? ??????? ???? ???? ??...???????

????? ?????????? ????...???? ???? ???? ????...???????...? ????...????

???? ???? ???? ????????? ?????? ???? ?????????? ?463-465

20> ???? ???? ?? ? ?? ???? ?248 ?? ?? ??? ????? ??

?365 ?? ?? ??? ????? ?465 See Hirano Kunio (KEJ, 1983: 147).

Hidden

Truth of History: About the Orgine of Japan (Recommanded

Homepage: www.EastAsianHistory.pe.kr) Hidden

Truth of History: About the Orgine of Japan (Recommanded

Homepage: www.EastAsianHistory.pe.kr)

The Yamato Kingdom:The First Unified

State in the Japanese Islands Established by the Paekche People

The Yamato Kingdom:The First Unified

State in the Japanese Islands Established by the Paekche People

The Japanese Islands Conquered

by the Paekche People the foundation myth: trinity

The Japanese Islands Conquered

by the Paekche People the foundation myth: trinity

Massive Influx of the Paekche

People into the Yamato Region

Massive Influx of the Paekche

People into the Yamato Region

Fall of the Paekche Kingdom and

Creating a New History of the Yamato Kingdom

Fall of the Paekche Kingdom and

Creating a New History of the Yamato Kingdom

King Kwang-gae-to’s Stele yamato

solideirs in the korean peninsula

King Kwang-gae-to’s Stele yamato

solideirs in the korean peninsula

Archeological Break:Event or Process

the late tomb culture

Archeological Break:Event or Process

the late tomb culture

They, Including Minister Soga,

Appeared Wearing Paekche Clothes

They, Including Minister Soga,

Appeared Wearing Paekche Clothes

Coming Across the Emotive Records

in Kojiki and Nihongi revelation of close kinship

Coming Across the Emotive Records

in Kojiki and Nihongi revelation of close kinship

|

|